The intelligence in artificial intelligence, a matter of poetics

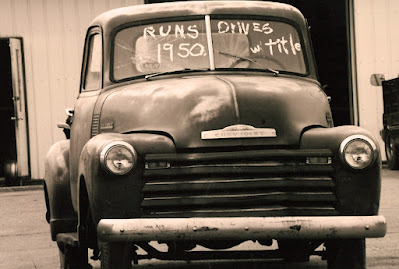

Only one question, one test of intelligence remains: Can a computer love? When I think of the communist poet of love, I think of Andrei Platonov, his love of people, his love of language, and his love of machines – his “aspiration to create a better, fairer world.” He wrote only one collection of verse, Blue Depths, but his fiction is more poetic in its imagery and its use of language, “[his] use of letters, archaisms, substandard vocabulary, and even handwriting. Platonov’s experiments in language and his interest in the physical fact of a text gained him an immediate audience.” Chevenger, his quixotic ramble through the heart of Civil War-torn Russia in search of the communist utopia, reminds me of the often ignored stretches of the Midwest from Wisconsin to Nebraska. The novel captures Platonov’s early ideals, embodied in the main character, Sasha Dvanov, who is trained in the operation of locomotives by Zakhar Pavlovich, a man who “so achingly and jealously loved steam engines that he watched with horror as they were run…. He figured that there are many people and few machines. People are alive and stand up for themselves, while a machine is a tender defenseless breakable being.” Is this love not unlike the affection Midwest farm boys once showed their first cars, christened with pet names like “Blue Balls,” while their fathers wrote letters to machinery companies about improvements made to tractors and other implements? Have we not somewhat lost this machine love when it comes to computers?

An excerpt from an article

in response to the misuse of words such as “intelligence” for computers and to the misuse of the label "poetry".